The Wandering Earth and the Ugly American

On Chinese blockbusters' hilariously unflattering depictions of Americans at the dawn of the new Cold War and the promise of post-Covid science fiction

I’ve largely lost track of the Chinese tech industry in the years since my brief stint in it – I hardly check my WeChat these days. But somehow, I watch way more Chinese movies than I did living in China.

In the time since I left, the number of movie theaters in China has actually more than doubled – movie-going being one of those quintessentially middle-class past-times being rolled out with successive waves of economic development emanating from the first-tier cities outward. And so have budgets for domestic movies.

A typical lineup at the multiplex, when I’d lived there, was a smattering of mainland romcoms and historical dramas, a Hong Kong kongfu movie, and one or two of of only glitziest, highest-budget action franchises from Hollywood like Marvel or Transformers.

Since then, it seems like a lot fewer of those movies from Hollywood are being approved. While China has always had talented filmmakers, it’s gotten gotten really good at funding and making the sort of expensive popcorn flicks it used to primarily import from the US.

What makes these recent mainland Chinese movies so fun to watch from an American vantage point is not just the increasing levels of craftsmanship and raw spectacle going into them (often with the help of Hong Kong talent) – but their cultural and geopolitical vantage point (which is very different from what we’re used to in Hong Kong movies). At best, they take on traditionally Western genres with an Eastern outlook, and at worst, they can appear a kind of wartime propaganda - like a Casablanca or Ohm Krüger — oddly commissioned during peacetime, which in some twisted way, is also pretty fun to watch.

As the US and China have both become increasingly xenophobic and nationalist in recent years, it is also amusing in some morbid sense to see how Americans are now being portrayed in these increasingly epic, globe-spanning stories Chinese filmmakers have gotten so good at telling.

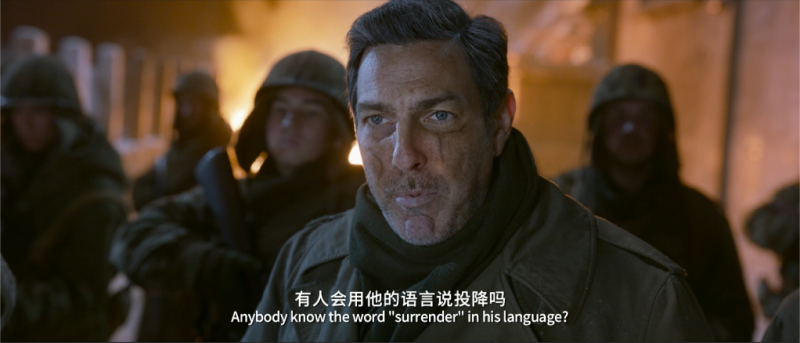

Take, most notably, 2021’s The Battle at Lake Changjin – a two-part war epic notable not only as the most expensive and highest-grossing Chinese movie ever produced, but as a Korean war movie that doesn’t feature a single Korean. It does, however, have lots of Chinese and American characters.

Between hagiographic, grandfatherly depictions of Chinese figures like Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai, and Peng Dehui, we also glimpse huge set-pieces of American bases and lengthly deliberations of key American figures like Harry Truman (complete with Resolute desk and “The Buck Stops Here” sign) and Douglas MacArthur (complete with corncob pipe). Changjin’s MacArthur is less Gregory Peck and more Darth Vader – his entrance always shot from below and accompanied by a sinister leitmotif. Then there’s plenty of scenes with G.Is doing apparently stereotypical American things like getting drunk, reminiscing about their mother’s broccoli casserole, looking at pinup girls, and, well, mostly getting shot at.

Lake Changjin was spearheaded by the legendary military-affiliated August 8th Film Studio, which, only years after the Korean War, first tackled these events in 1956’s Battle on Shangganling Mountain. Without anything like Changjin’s ensemble of international talent available in the 50s, the production made do with Chinese actors in whiteface and fake noses to play Americans.

Changjin is the latest in a series of many such patriotic movies, which, in order to be effective in shaping public opinion, have had to shed the appearance of state media and taken on more pop culture bonafides – forming the so-called “main melody” genre of entertainment. Changjin boasts a star-studded roster, with not one but three famous directors and top stars like Wu Jing (as the same guy he plays in every action movie) and Jackson Yee (as the requisite teen hearthrob).

Not all government-sponsored movies in China are of the patriotic variety. For instance, 2022’s Nice View, a project of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China, tells the story of an ophan (also played by Jackson Yee) who bootstraps an electronics recycling business in Shenzhen in order to pay for his kid sister’s expensive cardiatric surgery. It is the most touching and persuasive paen to capitalism I have ever seen – and I sat through all three Atlas Shrugged movies.

Conversely, neither are all nationalistic or party-line-toting movies in China government-sponsored. All movies must make it through various approvals to receive a permit for public showing and sometimes encounter resistance. When movies are made for even for entirely secular entertainment value, their creators still must think through what might get approved and still, like commercially-motivated filmmakers in any country, end up speaking to popular sentiment and topics in the current zeitgeist.1

Aside from war movies, there’s now a sub-genre of Chinese action movie usually set abroad in some ficticious third-world country. Like the mythic Jianghu realm in wu xia stories, these settings allow the writers to escape the constraints that might apply if they had been set in present-day China, where it would require more suspension of belief for the heroes to tumble through windows or lob grenades. I mean, they can’t exactly do that walking around Sanlitun, can they?

Wolf Warrior 2 is the most famous – it gave rise to the phrase “wolf warrior diplomacy.” It takes place in an unnamed Somalia-esque country beset by an insurgency led not by African warlords but by “Big Daddy”, an American mercenary played by Frank Grillo. He epitomizes evil, a caricature like some kind of American Fu-Manchu. He’s seen cussing, spitting, and shooting people when they say something disagreeable.

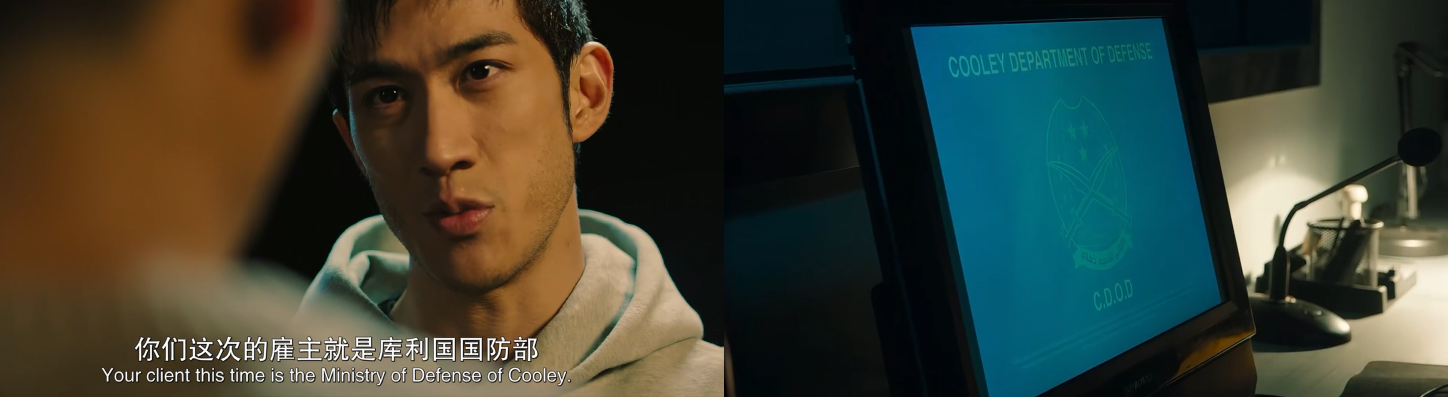

There’s the similarly-named “Wolf Pack” set in an ambiguously middle-eastern petro-state called – who approved this? – “Cooly” (it has its own coat of arms and everything). Then there’s the recent Homecoming, taking place in Numia.

In these sorts of movies, the African and… Coolean?… characters function largely as props for the Chinese heroes to save and the Americans, when included, as antagonists.

ENTER CHINESE SCI-FI

And now there’s some pretty great Chinese sci-fi, a genre that was, in all these years, entirely avoided in film and TV. Though there have been many noteworthy sci-fi authors in China recently, this foray has been conservative, a toe in the water – consisting almost exclusively of adaptations of Liu Cixin (of Three Body Problem fame)’s works. He sold off the rights some years ago and we’re now slowly seeing the results.

There have now been two movies based on Liu’s The Wandering Earth, a saga about humanity escaping a cosmic solar cataclysm by turning the Earth into a spaceship and, with the aid of giant engines built on every continent, piloting it to another solar system.

When I’d read the original novella, the backstory of humanity taking unanimous action to save the planet under the auspices of a “United Earth Government” and the sort of collectivist value system the protagonist takes for granted had distracted me. It seemed unrealistic and lazy, even, in a way that Star Trek’s Federation didn’t – the Federation at least came from the ashes of a eugenics war and required intervention from the Vulcans as humanity’s better angels. This seemed especially schmaltzy to me during an period of American sci-fi with a penchant for the dystopian and nihilistic – the era of the gritty reboot.

The first Wandering Earth movie doesn’t embellish much on this – nor is it particularly nationalistic – we’re led to believe the present Chinese state and Communist party has persisted into the future and that it, rather uneventfully, has worked in harmony more-or-less as a peer of the other nations of the Earth to help humanity avoid certain catastrophe. The story is tightly focused on the journey of the Chinese heroes, though there’s a token Russian cosmonaut, some English wording on computer screens, exposition shots with CNN chyrons, and an excursion to Indonesia to give its world an international flare.

That first movie had come out in late 2019, not long before the pandemic. Back in reality, as the pandemic unfolded, there was a pretty clear contrast across the world in how different countries handled it: Chinese local governments quickly enacted cordon sanitaire to contain the virus and Americans immediately politicized the issue and had a bunch of unhinged protests about wearing masks, which erupted into further culture wars leading into the elections. The reality of which system ultimately was more effective is more complicated when you add vaccinations to the mix, but the optics at the time in those early days couldn’t have more starkly illustrated the differences in values and politics.

The second Wandering Earth came out this year to great anticipation, shaped from the events of the intervening years. Satisfyingly, as a prequel, it speaks directly to this schism and embellishes that part of the original backstory I found unconvincing – how, exactly, do you get every country to pitch in and build giant engines and underground cities if we can’t even get our shit together on Covid and global warming in the present day? Where the conflict in the first movie was the classic “man against nature”, the second is squarely “man against man.”

When Hollywood came back from the pandemic, we saw movies like Don’t Look Up that also wrestled with this topic. When Star Trek Discovery resumed production after Covid, the Discovery crew had traveled a millenia to a galaxy disrupted by the sudden disappearance of the dilithium fuel for starships and the Federation a shadow of itself. Ultimately, Don’t Look Up’s asteroid, The Wandering Earth 2’s solar crisis, and Star Trek: Discovery’s “burn” all serve as celestial McGuffins to challenge humanity to move beyond the dismaying realities of waning state capacity, our loss of trust in institutions, and toxic tribalism revealed during our collective experience during the Covid pandemic.

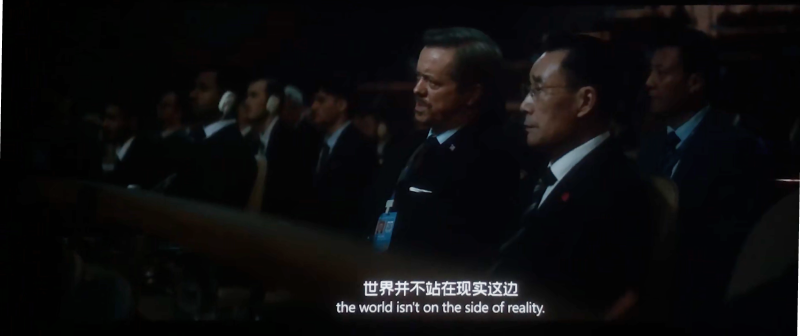

The Wandering Earth 2, like a lot of sci-fi sequels, brings some new characters. Its Jar Jar Binks comes in the form of Chinese ambassador Zhou Zhezhi, played with gravitas by veteran actor Li Xuejian, and obviously modeled after Zhou Enlai. We spend a lot of time with him and other diplomats on the floor of the UN (or is it UEG?) General Assembly in New York City.

Zhou butts heads on several occasions with Western diplomats. In one exchange, the United States ambassador (played by the same guy who plays General Almond in Lake Changjin) confides to Zhou that the American voters largely don’t support the idea of building giant turbines to move the Earth out of the Solar System and the Senate might pull funding. “More are questioning how much solving a crisis 100 years in the future should matter to people living now.”

Zhou persuades the ambassador, echoing Carl Sagan’s famous remarks on the “pale blue dot” image taken by Voyager. Zhou does not, of course, say what plan is polling well with the Chinese public because that does not matter any more in 2040 than it does today. Only Americans are hampered by infighting and the inefficiencies of democratic governance.

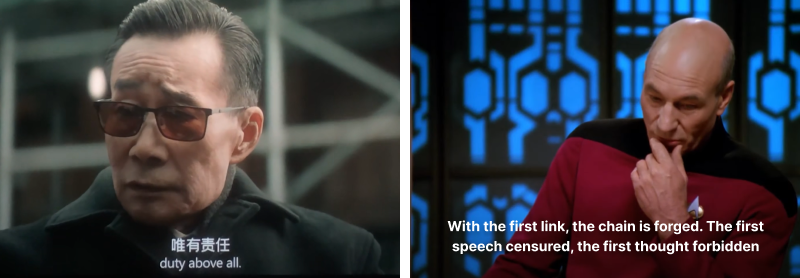

In other scenes, Zhou and other Chinese diplomats prattle on further about the need for courage, unity, and collective sacrifice. These reminded me of the kind of speeches Captain Picard would sometimes give on Star Trek TNG – though Picard’s were always about classical liberal values like freedom of speech and human rights (or, at any rate, android rights).

There are lots of scenes with Westerners pissing and moaning and otherwise holding up progress – underscoring that China, in the 2040s, is apparently the one that must lead the world in these sort of things.

When it’s not American diplomats raining on the parade, we see montages of Western mobs protesting whatever the current plot-point is (there are, of course, no Chinese protesters in the future). Several scenes get interrupted by a crazy white boy with a bomb:

Westerners also provide comedic relief, like when a cocky American astronaut tries unsuccessfully to hit on Wu Jing’s love interest, or when the security guard watching the space elevator gets distracted by a game on his phone. Later on, when a technique involving quantum computing and robots is perfected to build the Earth Engines, we see schlubby Western blue collar workers – like those stereotyped on South Park or shown in American Factory – whining “don’t let the robots take our jobs!”

There’s also a whole subplot on a competing bid to solve humanity’s problems – the “Digital Life Project”, a plan to upload everyone’s souls to the metaverse so they can live on while their corporeal bodies are engulfed by the sun. It is led by Indian scientists (China is not on very good terms with India these days either). At various points, Digital Life Project fanatics lead terrorist attacks against space elevators, the Earth Engines, and the UN building in New York, with diplomats scrambling for cover, reminiscent of the January 6th attacks.

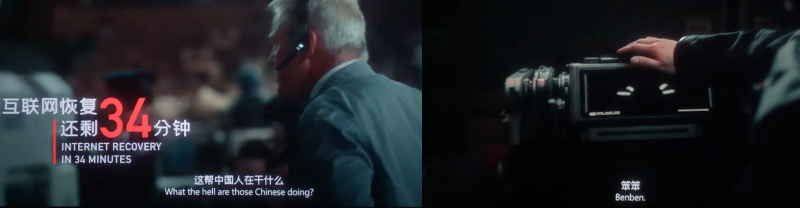

Another, more fanciful subplot follow a crack team (and their oh-so-merchandizable robot dog sidekick, Ben Ben) diving into an waterlogged Beijing to restore the root servers at the heart of the world’s Internet infrastructure. This seems immediately silly not only because of the Internet’s distributed nature but because, in the future, the world putting the Chinese in charge of the Internet would be like putting the British in charge of the food. We’d succumb to meat-pies before the solar flares got to us.

Despite all this, Wandering Earth 2 stops well short of being “Changjin In Space.” In the movie, the Americans, as Churchill once observed, get around to doing the right thing after they have exhausted every possible alternative.

There are thematic similarities, though. Changjin has all these awkward asides from the action where the soldiers all but break the fourth wall to opine to the audience about how they are fighting the Americans now so that their children do not have to fight them in the future. Sacrifice is a major theme, with the series bookended by the Wu brothers returning from war to their hometown with cremation urns. There’s a key plot point in Wandering Earth 2 where the elder Chinese astronauts propose that the astronauts above age 50 undergo the task of blowing up the moon which – for plot device reasons – can only be done manually, sitting next to the nukes on the lunar surface. For all the current generation cares, the Fuchilin Pass might as well be the moon.

Throughout both movies, Frant Gwo makes loving homage to American sci-fi, particularly the works of Stanley Kubrik, with HAL 9000 being the clear inspiration for the “MOSS” AI and a final scene where Zhou gets up from his wheelchair undeniably a reference to Dr. Strangelove. (Come on, even he goes to live in the underground cities after that)

The Wandering Earth 2’s meditations on factionalism, digital escapism, and the possibilities of AI are fresh and topical. And it’s full of inventive little embellishments that form a fully-realized and original vision of the future – like the distinctive “doorframe” robots that follow UEG soldiers around and a haunting depiction of what it’d be like to be stuck in the metaverse as a quantum simulacrum.

Liu’s Three Body Problem has also made it to the screen this year, with Tencent releasing the first season of its adaptation. Unlike the Wandering Earth movies, it faithfully follows the first novel with little embellishment, largely leaving intact its view of the politics of the Cultural Revolution. It has a great cast bringing life to the characters in the book – I particularly enjoyed the buddy cop dynamic between Wang Miao and Shi Qiang.

We see the usual menagerie of foreign actors in the show’s Chinese-led UN-equivilant debating how to deal with the looming alien invasion. And David Woodley’s portrayal of Mike Evans – albeit another stock evil American character – speaks Mandarin and brings more “badass” to the role than “bad.” The sequence where – in the game world – John von Neumann and Gallileo build a computer with Chinese soldiers as logic gates is particularly delightful.

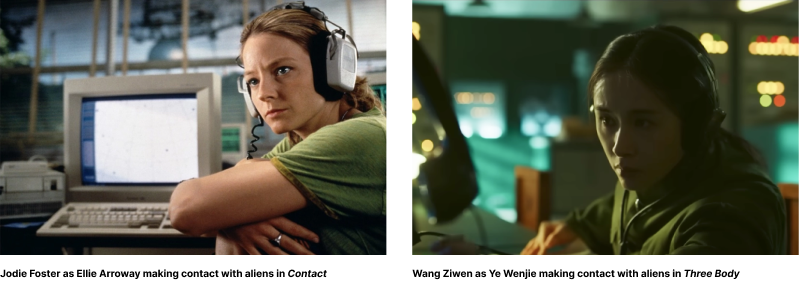

Seeing this sort of stuff makes me re-evaluate some of the other sci-fi I’ve seen. There is something slightly uncanny and unnerving about watching them – I’d taken for granted American pop culture’s relative narrative monopoly on the future. When aliens make first contact, why ought the American president (or Zephram Cohrane) be involved? Why not, as in Three Body Problem, a secretive unit of the Chinese army? Why ought alien tongues be translated into English? (in Three Body, Chinese and Esperanto are used)

To the extent the original Star Trek was a pioneering in its humanism, it was still partisan and envisioned the future with a Western frame of reference. Even Mr. Sulu was a composite character, from no particular Asian country. Conflicts with the Klingons and later Cardiassians were analogs for the U.S.S.R. in thinly-veiled allegories dealing with Cold War anxieties.

A lot of the sci-fi I’ve seen in recent years are kind of downers, too – between Interstellar’s post-decline, dust-bowl US and Ad Astra’s mopey melodrama. For All Mankind, while excellent, is a backward-looking work wistfully imagining what might have been. Extrapolations comes from the same defeatist, finger-wagging place as Don’t Look Up. Picard’s first season – released right before the pandemic – saw the Romulans’ home star go on the fritz like the Sun in Wandering Earth – but the Federation declines to intervene, the Romulans perish, and this just becomes fuel for then-admiral Picard to become disillusioned. It seems to be assumed in sci-fi, now, that when some existential crisis occurs, humanity’s leadership and institutions will shit the bed. (Though Three Body, is at times, rather misanthropic in its outlook, too).

As author Ursula Le Guin once asked in an interview with The Nation, “Don’t readers ever get tired of being told that the world is coming to a nasty, ugly end and only a very few people will survive, by luck and by violence?” There’s now a literary movement in sci-fi called “Solarpunk” that rebels against this tendency, though we haven’t seen much of the sub-genre make it to the big screen. The Wandering Earth, while optimistic, probably wouldn’t count as solarpunk as these works emphasize harmony with nature and The Wandering Earth is about kicking nature’s ass.

In the real world, humanity does face existential crises, between global warming and more pandemics, and it isn’t clear a single superpower can solve them. Having more sci-fi entertainment from around the world grappling with these topics from all cultural vantage points seems like a good thing. I just wish they’d be a little nicer to Americans sometimes, even if we don’t deserve it.

-

For example, Guan Hu’s excellent Mr. Six, released in 2015 during the time of political purges of party leaders, tackles the topic of government corruption and concludes with the corrupt mid-level official going to jail and top rungs of government, along with the titular Mr. Six, vindicated, all set to a cheery montage. At the time it came out, a friend told me he could hardly believe such a story could make it past censors; my thought was that if I were some Rupert Murdoch-like figure in China, that would be precisely the kind of movie I’d want people to see. There’s also been a TV series In the Name of the People – often compared to House Of Cards – in a similar vein that I haven’t had time to watch. ↩